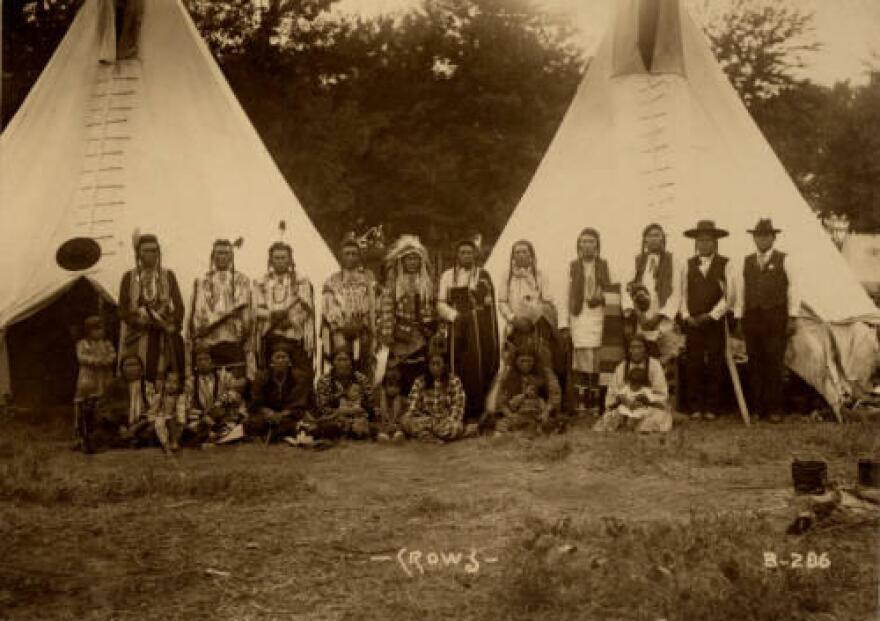

The Indian Congress, held in 1898, was the highlight of the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, otherwise known as the Omaha World’s Fair. Five hundred representatives from 35 tribal nations attended the congress, making it the largest gathering of Native Americans of its time.

Enter Frank Rinehart, the official photographer of the Trans-Mississippi Exposition. Rinehart and his assistant Adolph Muhr captured thousands of images over the five-month event, held in what is now North Omaha on 184 acres, some of which today is Kountze Park. But it’s the portraits of Indian Congress representatives, taken in the closing weeks, that became his legacy.

Rinehart’s Indian Congress photos are the subject of Wendy Red Star’s exhibition now on display at the Joslyn Art Museum through April 25. Red Star is a scholar, multimedia artist and member of the Apsáalooke (Crow) Nation. One-hundred-and-twenty-three years after the exposition’s close, she has reunited the members of the Indian Congress in the Joslyn’s Riley CAP Gallery using Rinehart’s photos.

“Those images just drew me in right away,” Red Star says. “They're spectacular. They're beautiful. I think you just can’t deny the beauty.”

The exhibition contains hundreds of Rinehart’s Indian Congress portraits, meticulously hand-cut by Red Star and arranged on 18-foot tiered tables decorated with American flag bunting. It’s a tongue-in-cheek nod to the imperialistic intentions of 19th century world’s fairs.

“Once I got past 100, I was like, there's just a lot,” she says. “There's a lot of photos. And that's really what I wanted to convey, is just the amount of Native people at the Indian Congress. It was just so important for me to have that amount of different Native people represented, and then just for the viewer also to have time to kind of sift through and digest everything.”

A separate table, decorated in gold-tipped goose feathers, stands at the front of the room. The photos on this table were also taken by Rinehart and Muhr, but not at the Indian Congress. A year after the congress’s end, Rinehart and Muhr traveled to the Crow Reservation on Apsáalooke homelands in Montana. Their visit was likely brought about by Alexander Upshaw, a Crow interpreter who was also an Indian Congress representative. Red Star says she didn’t know about the connection between Rinehart and her hometown prior to starting the project.

“It's just kind of like this amazing web that is highly addictive,” she says. “It's all interconnected. It's like a little domino effect....Once I start kind of pulling on a thread, it connects to this other thing, and it's sort of all interwoven.”

Annika Johnson is the associate curator of Native American art at the Joslyn and the curator behind the Rinehart exhibition. She and Red Star collaborated on much of the research process. In 2019, Red Star visited Omaha to embark on a mini expedition with Johnson. They found Rinehart’s gravesite at Forest Lawn Cemetery in northwest Omaha. They tried to access the seventh floor of the Brandeis building, now home to apartments, where Rinehart kept his photography studio. And they made a stop at the Omaha Public Library, which is home to a vast collection of Rinehart’s prints from the Trans-Mississippi Exposition.

“He's a good photographer, but at the same time he has profile portraits in there, and that stems from this ethnographic photography convention of trying to capture the, you know, air quotes ‘race’ of an individual,” Johnson says. “And so there's a really dark anthropological legacy in that portraiture convention. So the whole thing is just, you know, it's full of tensions, and there's a lot to unpack and to talk about in terms of the legacy of image-making of colonization. This is a really fraught moment in history. But to have this archive in Omaha is really incredible; to have this group of photographs be together, representing this particular moment in time.”

Rinehart and his photos have a complicated history. The Indian Congress itself was first and foremost a money-making venture. The congress members spent the days of the fair selling artisan goods to the mostly white visitors and putting on sham battles for their entertainment. Rinehart himself made lots of money selling prints and postcards to people who lived on land stolen from the photos’ subjects.

Additionally, world’s fairs have a genocidal history. Human zoos and other exploitative ethnographic displays were fixtures at expositions in the United States and Europe through the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In addition to the Indian Congress, the Trans-Mississippi Exposition also featured an “Old Plantation,” as well as “Chinese Village” and an attraction called “The Streets of Cairo.”

“I always feel like you need to talk about these things,” says Martha Grenzeback, a genealogy librarian with Omaha Public Library who assisted Red Star during the research process.

“I hate to discover that people have never heard about some of the things that were a big part of Omaha history at one point, because I think it just makes it easier to black out parts you don't like, forget that they happened. So I think it is very important that we keep this in our memory. And I love what Wendy did with it, because she makes all those photographs into people.”

There are parts of Rinehart’s legacy that have benefited the Native people he photographed. Unlike his more famous counterpart Edward Curtis, Rinehart wrote the names of his sitters on the photos. This was likely for taxonomic purposes, but it was a blessing for researchers and descendants of Indian Congress delegates,

Alicia Harris is both. She is an art history professor at the University of Oklahoma who got her PhD from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln with a thesis about indigenous identity in Rinehart’s photography. Her great-great-great grandfather was an Assiniboine band chief named Red Dog who sat for Rinehart at the congress.

“I think that any time any Native person is claiming their own image, their own likeness, or control over how that's used or understood is an act of resistance,” Harris says. “To say these are people first of all, and these people have a story beyond just this image, right? We're not just wallpaper. We're human beings that have these lives that go beyond what's represented here in this photograph. It's absolutely an act of resistance, and it's hard to do. I think there's a lot of imagery out there that is the opposite of that. And so anytime somebody is able to kind of make a reclamation of that I think is powerful.”

For her part, Red Star says her work is about asking questions, not answering them. She says she hopes visitors take a moment to consider the power of this reunion as they gaze upon images of the Indian Congress

“It's our history,” she says. “I can't tell you how much I have to repeat that, like telling non-Native people, people who live in the U.S., this is their history. It's not segregated. You know, it didn't just happen to Native people. It's what made you, you, and your experience living here. So that's why those images are important...like, how incredible is it that the Indian Congress was there in Omaha? And you being in Omaha, and having that chunk of history there? Like, I was blown away to know that knowledge. So that's why those photos are to me — you just have to recognize that they are super complicated. They're complex. But they are very important documents. They're important documents. And if you were to ask me, ‘Would you rather have had Edward Curtis not done that project? I'd say, ‘Hell no. Hell no.’ That is important information, important photos of my community. And like I said, I have stuff to say, I have stuff to ask, I have stuff to ask my community about those images that is important to this history.